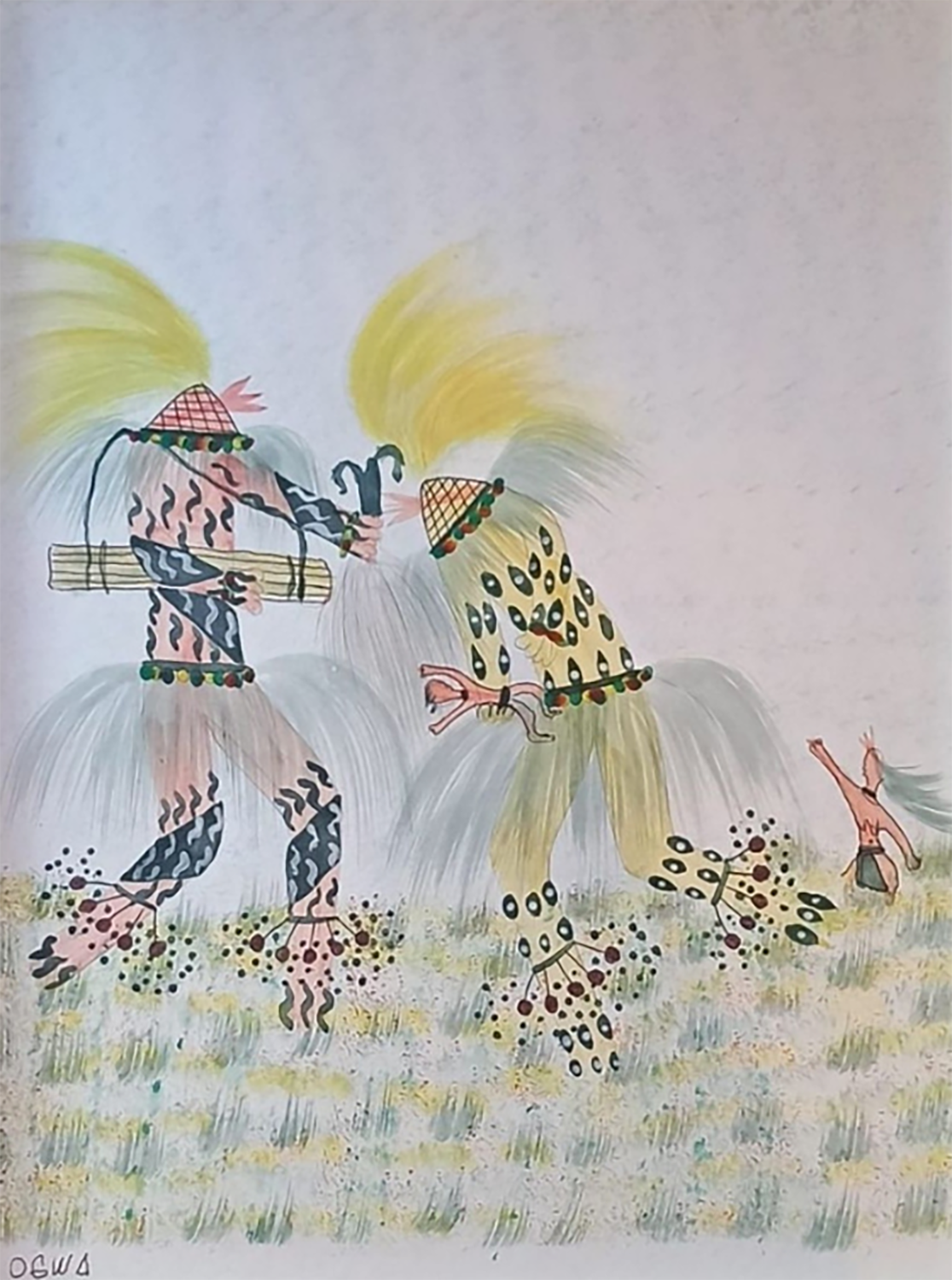

OWGA

Bio

Born in Puerto Caballo, north of Bahía Negra, in the Paraguayan Chaco, in 1937. She belongs to the Ebytoso Group of the Ishir–Chamacoco ethnic people. Her clan is Posháraha. Indigenous name: Ógwa. She was initiated into Chamacoco culture at the age of 12.

In 1989 she began drawing scenes from Chamacoco culture, supporting the work of national and international anthropologists.

In April 1994, she created the illustrations for the book *“Desde el encendido corazón del monte”* by René Ferrer.

In September, she exhibited her work at the OIPIC venues, sponsored by UNICEF. In November, her designs were used for OIPIC’s Christmas cards. In October, she held an exhibition at the Yatay Art Gallery. In December, she was awarded the “Genaro Pindú” Prize, granted at the Bosque de los Artistas under the organization of Hernán Gugiari.

In 1996, the Sub-Secretariat of State for Culture organized an exhibition of her colored designs at the Museum of Fine Arts in Asunción.

Statement

The life of Ógwa —an artist of the Ishir-Chamacoco people— exemplifies the profound tensions experienced by today’s Indigenous societies, compelled to move constantly between two worlds: their own, guided by ancestral communal norms, and the dominant Western culture, with its new aspirations, prestige symbols, and inequalities. This cultural clash marked his existence from childhood. Born to an Ebidóso woman and a white deserter from the Chaco War, he was marginalized within his own family as an illegitimate child, subjected to mistreatment and emotional exclusion. His true sense of belonging emerged instead among other Ishir youths and elders, who trained him in rural labor and the harsh realities of life in the Chaco.

His biography unfolds as a sequence of intense episodes: early work in logging camps, periods of domestic service in white-owned ranches, his marriage to Wéztak, constant efforts to secure a livelihood through hunting and temporary jobs, as well as a series of tragedies—economic losses, the abduction of his daughters during floods, the murder of a son-in-law and later a son, and an advancing eye disease that eventually led to blindness. From 1989 onward, amid this material and emotional decline, painting became his path to personal and symbolic recovery.

Yet his artistic career also developed within an unequal framework. Although his talent was acknowledged, his work was consistently assessed through Western categories such as “naïve art,” and—under the peculiar logic of a colonial market—his vibrant and culturally rich production was repeatedly undervalued.

Ógwa thus emerges as a figure shaped by resilience, memory, and the conflict between identities. His trajectory illuminates, with deep human force, the contemporary dilemmas faced by Indigenous peoples and the ambiguous space they must navigate between tradition, marginalization, and creative expression.

2.5 x 4m / 98.4 x 157 in